Blooms of planktonic algae, or 'red tides', have been seen since biblical times. Most are harmless and merely colour the water, while others can produce toxins that may have a serious effect on the surrounding marine life. Blooms in areas where fish and shellfish are farmed can cause serious economic losses.

There are around 2,000 species of planktonic algae, called dinoflagellates, in the world. These can cause red tides and some can also produce potent neurotoxins that can poison humans if consume fish contaminated with them.

Other algae are also implicated in fish kills, including Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) and Prymnesium parvum (Prymnesiophyta). These are two relatively common algae that secrete compounds into the water, causing large and recurring numbers of fish deaths in Western Australia.

Dense algal blooms, either toxic or non-toxic, can cause oxygen depletion in the water, resulting in the death of fish. Some members of a major common group of algae called diatoms can cause physical obstructions that clog the gills of fish and shellfish, either by producing a mucous-like substance or by penetrating gill membranes.

Some of the more common types of algal poisoning that can happen in fish and humans, along with advice about their symptoms, treatment and prevention of infection, are outlined below.

Ciguatera poisoning

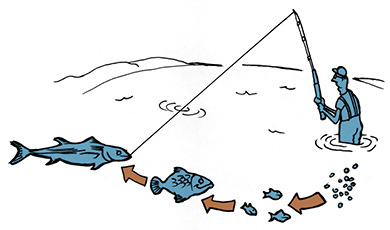

Ciguatera poisoning in humans and domestic animals is caused by potent neurotoxins thought to be produced by bottom-living dinoflagellates including Gambierdiscus toxicus. These toxins build-up in the food chain, starting from small fish grazing on algae on coral reefs which are then eaten by larger top-order predators such as coral trout, red bass, chinaman fish, mackerels and moray eels, where the toxins go into their organs.

How the ciguatera toxin ‘bioaccumulates’ up the food chain – moving from algae to fish to humans

Ciguatera poisoning is believed to affect up to 50,000 people a year around the world. Tropical countries such as French Polynesia report thousands of cases every year. In Australia almost all ciguatera poisoning is results from fish caught in Queensland or the Northern Territory. However, the most extensive ciguatera poisoning incident in Australia reportedly took place in Sydney in 1987, when 63 people were affected.

Symptoms in humans and treatment

Mild cases of ciguatera may result in poisoning, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. More extreme cases can result in numbness and a tingling sensation in the body’s extremities. Other symptoms include the reversal of hot and cold sensations, low heart rate and blood pressure, rashes. There is also a risk of death through respiratory failure so it is vital to consult a doctor as soon as possible.

Preventing infection in humans

Avoid eating small fish that graze on algae on coral reefs and large top-order predators, such as coral trout, red bass, threadfin sea perch, mackerels and moray eels, which feed on them. In particular, treat oversize fish with suspicion. Avoid eating the viscera (internal organs) of any tropical fish species.

Paralytic shellfish poisoning

Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) is probably the best known of all the shellfish poisonings. Around the world there have been over 100 reported deaths and several thousand illnesses attributed to ‘PSP’.

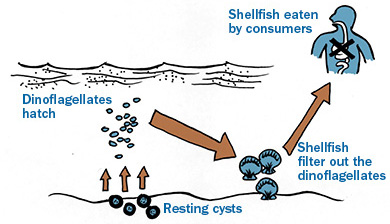

Around 20 species of dinoflagellates have been implicated in producing the alkyloid toxin saxitoxin that accumulates in shellfish. Saxitoxin, actually a group of at least 18 toxins, is a potent neuromuscular blocking agent that finds its way through shellfish to humans.

How Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning is given to humans

Dinoflagellate species known to produce this toxin include Gymnodinium catenatum, Alexandrium catenella, A. minutum, A. tamarense and Alexandrium. Most of these dinoflagellates have not been shown to be directly toxic to fish or shellfish.

Symptoms in humans and treatment

In mild cases of PSP there may be tingling or numbness around lips (spreading to face and neck), headache, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea . In more extreme cases there could be muscular paralysis and respiratory difficulty, potentially resulting in death due to respiratory paralysis two to twenty four hours after ingestion. It is vital to consult a doctor as soon as possible.

Diarrhetic shellfish poisoning

Diarrhetic shellfish poisoning (DSP) was first discovered in 1976 in Japan. Between 1976 and 1982 there were more than 1,300 diagnosed cases with the algae (armoured dinoflagellates) Dinophysis fortii and D. acuminate identified as responsible.

Eating shellfish contaminated with diarrhetic shellfish toxins (akodoic acid, dinophysistoxins and pectenotoxins) causes severe gastrointestinal problems. Although no deaths have been reported, the symptoms can last for two to three days.

Symptoms in humans and treatment

In mild cases of DSP, after 30 minutes to a few hours there may be diarrhea, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. In more extreme cases, chronic exposure can result in tumours developing in the stomach. It is vital to consult a doctor as soon as possible.

Amnesic shellfish poisoning

Amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP) was first discovered in 1987 in Prince Edward Island, Canada, resulting in three deaths and 105 cases of acute human poisoning. Although the problem does not appear to have reached Australia, other strains of the diatom responsible have been identified in Australian waters.

The amnesic shellfish toxin, domoic acid, is produced by the diatoms Nitzschia pungens f. multiseries and Nitzschia pseudodelicatissima which accumulate in shellfish and affect their consumers.

High-performance liquid chromatography or mouse bioassay techniques can be used to detect the toxin. Shellfish containing more than 20 parts per million domoic acid are considered unfit for human consumption.

Symptoms in humans and treatment

After three to five hours, mild cases can result in nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal cramps. In extreme cases, chronic exposure can result in tumours developing in the stomach. It is vital to consult a doctor as soon as possible.

Preventing infection in humans

Avoid eating shellfish in areas where 'red tides' of algae are known to occur. Cooking shellfish, and discarding the cooking fluids afterwards helps to reduce the amount of poison that could be ingested. Affected shellfish cannot be identified visually. If in doubt, don't eat it!

If there is any possibility of poisoning from shellfish from a particular area or place, alert public health authorities so samples can be tested.

Gill damage and irritation

Certain species of algae can seriously harm fish and shellfish by producing mucus that can clog the gills and cause suffocation, or mechanically obstruct and damage the gills.

Several species of diatoms within the genus Thalassiosira form jelly-like masses that have been noted as clogging the gills of farmed oysters in Japan. Gelatinous Thalassiosira blooms have been seen in New South Wales and the Gulf of Carpentaria. One prymnesiophyte, Phaeocystis pouchetii produces acrylic acid that is highly irritating to fish gills, as well as producing mucus that can foul fishing nets.

Although non-toxic to fish, the diatom Chaetocerus convolutus can cause fish deaths when its setae (bristles) break off and penetrate the gill membranes. Small fish are affected first. Death is caused by capillary haemorrhage, suffocation from over-production of mucus and possibly from secondary infections. The setae can also induce multiple granulomas in more chronic cases.

Algae that leave a bad taste

Some algae and diatoms can impart bad flavours or bitter taints to shellfish.

In 1987 in Port Phillip Bay, Melbourne, there was a bloom of the diatom Rhizosolenia chunii and three species of shellfish within the bay (mussels, flat oysters and scallops) developed a powerful bitter taint. The taint was so persistent and unpleasant that the mussels from the bay were unmarketable for seven months, causing a loss to industry of approximately $1 million.