The western rock lobster is one of the family of ‘spiny’ lobsters, colourful and protected by a strong carapace. They are sometimes called ‘crayfish’ or ‘crays’. Its scientific name is Panulirus cygnus. The species is the target of WA’s largest and most valuable fishery. A crucial element in predicting catches is an annual sampling program that looks at the abundance of late larval-stage lobsters (puerulus) settling on inshore reefs along the west coast between August and January each year. This puerulus settlement index has always shown a strong correlation with catches of lobsters three and four years later.

The spiny lobster family gets its name from two big rostral spines and hundreds of tiny forward-pointing spines covering the carapace. Their long antennae are used for navigation, self-defence and communicating.

They can live for more than 20 years and grow to weigh 5 kg. But due to fishing rules, fishers rarely catch animals heavier than 3 kg.

When temperatures are cooler they mature at six to seven years old, when their carapace reaches a length of about 90 mm. In warmer water they mature at smaller sizes, usually at about 70 mm.

Distribution and habitat

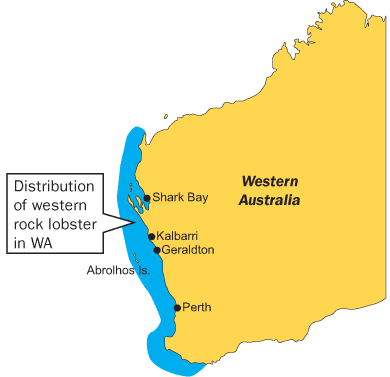

About eight species of rock lobster live in WA waters but the most abundant by far is the western rock lobster. They are a temperate species, only found on the continental shelf off the coast, with most living between Perth and Geraldton.

Lifecycle

Rock lobsters mate in late winter and spring. The male attaches a packet of sperm, resembling a blob of tar (generally called a ‘tarspot’), to the underside of the female between the hind-most pair of legs.

When females release their eggs, they also release sperm from the tarspot by scratching it. The eggs are thus fertilised as they are swept backwards and become attached to sticky fine hairs on the swimmerettes beneath the tail. Females carrying eggs are known as ‘berried’. The eggs hatch in four to eight weeks, depending on water temperature, and release tiny larvae, two millimetres long, into the water.

The larvae are called phyllosoma because of their leaf-like shape. They drift offshore and spend nine to 11 months in a planktonic state. They grow in a series of moults. Most stay 400 to 1,000 km offshore. The majority die but the survivors are eventually carried by winds and currents back towards the continental shelf.

The late-stage larvae undergo a moult that totally changes their appearance. They become miniature transparent rock lobsters known as pueruli. They are about 25 mm long. At this time they swim across the continental shelf, with help from prevailing currents, from deep waters onto onshore reefs – a distance, in some parts, of 60 km. They don’t eat on the way but are powered entirely by energy preserved from their larval phase. Many are eaten by predators or are not carried close enough to the onshore reefs by currents to allow them to ‘settle’ into their new lives as lobsters. Within days of making themselves at home on the onshore reefs, the pueruli develop the red colouration associated with western rock lobsters.

The pueruli grow to become juvenile rock lobsters through a series of moults. These juveniles feed and grow on the shallow onshore reefs for the next three or four years.

At this point, the lobsters undergo a synchronised moult in late spring. They change their normal red shell colour to a creamy-white/pale pink. The lobsters are then known as ‘whites’, until they return to their normal red colour at the next moult a few months later. The whites’ phase is a migratory phase. Once their new lighter-coloured shell has hardened, they set out on a two-pronged migration. Most head west and undergo a mass migration into deeper water, where they resettle on deeper reefs. A small percentage makes a longer migration to the north, usually following the continental shelf. In large groups, the lobsters trek at night, until they reach the spawning grounds, occasionally a hundred or more kilometres away from where they started and in water up to 100 m deep.

Diet and predators

Their food contains a wide range of items such as coralline algae, detritus (dead and dying marine matter), molluscs and crustaceans.

Juvenile lobsters are eaten by a number of fish species. As adults they are prey for octopus and a variety of large fish. They can regrow legs and antennae lost as a result of skirmishes with predators.

Illustration © R. Swainston/www.anima.net.au